See a preview of my novel, Underground, in the National Post.

Author: Antanas Sileika

The Lands Between – Part Two

Alexander Prusin’s The Lands Between is a study of the lands between Germany and Czarist and Soviet Russian from 1870 to 1992.

The map above, of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, loosely covers the area that both he and Timothy Snyder write about.

I’ve discussed his particular take on the postwar anti-Soviet partisan resistance in that area, but let’s step back now in order to get a sense of his overview.

He wonders why this area was so violent between 1914 and 1953. In effect, this shorter period covers the time of the fight for independence in those lands, as well as the independence period, and invasions from Germany and the Soviet Union and the Holocaust and the resistance after WW2.

The places were most violent when they tried to break away, and they were unstable because of ethnic tensions and economic backwardness.

Although he is not entirely in favour of the imperial regimes before WW1 and the Soviet Union after WW2, Prusin seems to imply that at least these lands between were less violent then. This assertion seems odd to me, given that the German and Czarist (later Soviet) forces were the ones that initiated the violence in the first place. At times, he sounds like he is blaming the victim, although it is certainly true that victims can also be perpetrators.

He is certainly right that the religions professed in the area were Lutheran, Roman Catholic, Eastern Orthodox, Uniate, Jewish, Karaite and other sects, and languages were as many or more. Before WW1 in Lithuania, the government activity happened in Russian, culture in Polish, some business and most Jewish home life in Yiddish, and farm and peasant life in Lithuanian.

These lands were multicultural avant la lettre, but not in a good way, according to Prusin. Current expressions of multiculturalism are usually deemed as positive. In the place and time described, the different confessions and linguistic groups cooperated when times were good, friction turned to fire when times were bad.

Interestingly, Prusin accuses the state of being the prime instigator of violence by encouraging latent hostilities. He does not exclude Soviet and German states, but neither does he limit the blame to those two.

And controversially, he says that large-scale collaboration was required to make the German and the Soviet occupations work. I have italicized the second part of the last sentence because traditional understanding of the term collaboration in the West put it solely in the Nazi camp. Prusin is saying that one could collaborate with the Soviets as well. There is nothing new in this understanding in the East, but it might be new to Westerners.

Prusin also states that the local population had no control over political and social processes.

One item that Prusin finds consistent is that Jewish communities were singled out as targets in the Czarist, independence, and wartime periods.

Particularly in the first days of the Holocaust, Prusin sets out this scenario: As the Soviets retreated under the German attack in 1941, they instituted a scorched earth policy and began mass executions of prisoners, usually local elites (teachers, politicians, policemen the Soviets had arrested earlier). These massacres were carried out in a gruesome fashion.

As I said to a friend of mine, people have just begun to understand about Katyn – they are just beginning to know that there were many more murders like that one, and they remain unknown in the West.

Due to the Soviet violence (and the mass deportations of just a week before), says Prusin, the German were greeted with genuine enthusiasm by non-Jews. Then the mutilated bodies of the former Soviet prisoners became public knowledge, and vengeance was twisted to be visited upon the Jews. However, violence upon the Jews was also initiated in places here there was no Soviet violence. Furthermore, nationalists envisioned a fight against communism as a fight against the Jews, and so we end with mass killings of Jews by many, many local German collaborators. Most active among them were policemen and others who had been imprisoned under the Soviets or lost relatives to them.

This point reinforces Timothy Snyder’s thesis (in Bloodlands) that the violence was worst where German and Soviet regimes overlapped.

In the postwar era, peoples and borders were moved to make homogeneous areas. The removal of multiculturalism, as we understand it, led to stability (not a solution we like to think about in multicultural Canada).

The violence in that part of the world, says Prusin, was so bad because it was initiated by the state and exacerbated by popular participation. In other words, it was total war.

Prusin states that things have calmed down in the region, but there are still dangerous historic legacies. First, the new countries (Baltics, Poland and Ukraine) have attempted to define themselves in terms of territory, ethnicity, and citizenship as they did after WW1. Indeed the Canadian writer, Anna Porter, has pointed out that the right wing is rising in central Europe, and signs of right-wing extremism are rising in the borderlands as well.

Second, the entire area is dependent on Soviet natural resources. Therefore, although the states are democratic and independent, they are torn between the globalization of the West in the EU and subservience to the East’s oil and gas.

The place remains inherently vulnerable to outside forces.

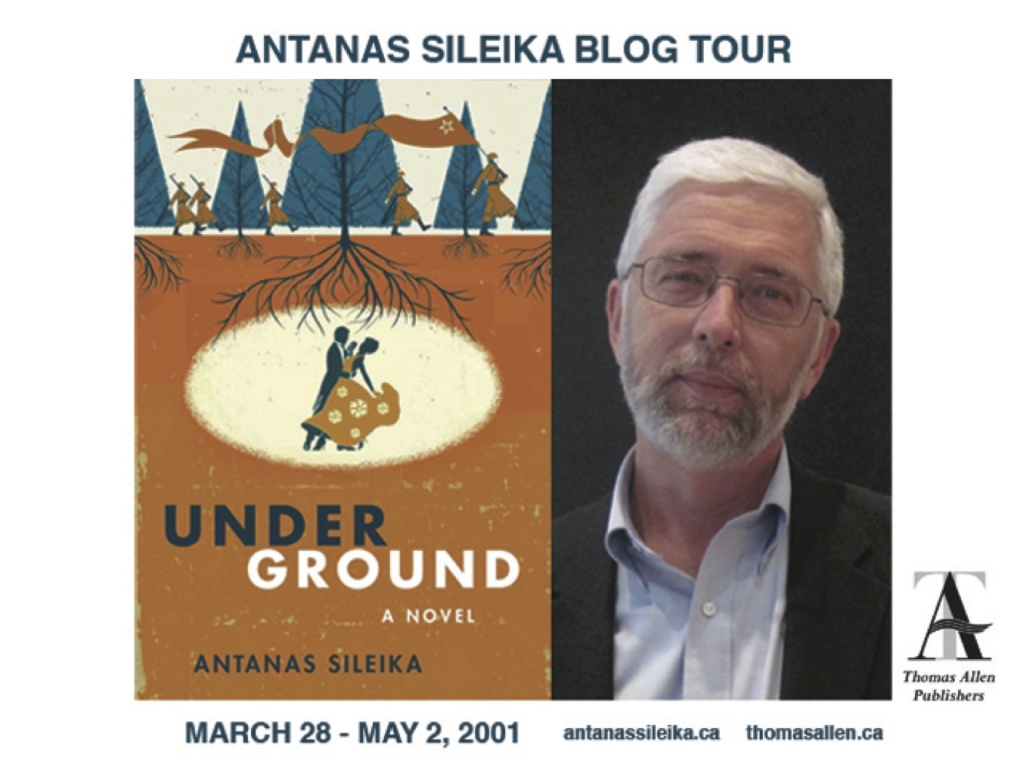

Blog Tour Now On

Underground is a historical literary thriller with elements of espionage and romance.

It’s set a very short time ago, just after the second word war, but in a part of Europe whose stories are untold and whose geography is obscure to most of us on this side of the Atlantic.

What are lovers in this place and time to do when history crashes into their personal desires and private lives?

I’ll be on a blog tour for the next couple of months, being reviewed and interviewed, so look for me and for talk about the book at the links down below. Some of the dates will follow later.

And on a final personal note, I wrote this novel trying to make it something a reader could easily fall into and live happily with for a few days, so I hope that turns out to be the case for you.

To start you off, se Eva Stachniak’s detailed interview at the first link below. I have the first three linked – the others to follow.

Eva Stachniak – currently available

The Afterword – The National Post, March 28 to April 1

That Shakespearean Rag – currently available

Open Book Toronto – currently available

Rob McLennan – forthcoming

Stepping back for a Long, Hard Look

A new overview of the territory between Russia and Germany has just appeared, called The Lands Between, (Conflict in the East European Borderlands, 1870 – 1992), by Alexander V. Prusin.

This history covers some of the same territory as Timothy Snyder’s Bloodlands with a few differences. For one, Prusin’s book is almost three times more expensive than Snyder’s costing a hefty sixty plus dollars in Canada.

Also, the historical range is longer, taking us back to the time before WW1 when the area was dominated by three powers – Czarist, German, and Hapsburg, and continuing to 1992.

As well, Prusin is considerably less sympathetic to the inhabitants of these lands, depicting them as inhabited by squabbling ethnic and religious rivals. Pressed by either Germans or Soviets, these rivalries became exacerbated and murderous, with the Jews the major but far from only victims.

Curiously, the least troublesome era in Prusin’s history seems to be the time before WW1, when religious and ethnic rivalries were controlled by the old empires. By implication, he seems to be saying these are areas guilty of irredentism when not suppressed by outside powers, yet the outside powers were trying to mold the area to their own image (in the case of the Czarist lands, by imposing the Cyrillic alphabet and orthodox Christianity).

The part of the history which interests me most is this text’s take on 1944-1954, the era of the anti-Soviet underground resistance. Prusin characterizes this period as one of civil war between collaborators with the Soviet regime and those who opposed them. As happened all too often in this part of the world, brutality upon brutality led to escalating violence until one side won, in this case, the Soviets.

Here’s a bit more detail on that – as the local partisans fought against the Reds, they forbade locals to take up positions of responsibility in the new Soviet administration. When collaborators did so anyway, the partisans attacked them. These attacks led to counterattacks by the relatives of deceased collaborators, backed by the Soviet army and secret police. In Lithuania, these Soviet forces numbered 12,000 security personnel and 40,000 – 60,000 troops.

This claim is slightly problematic because it begins with the attack by the partisans rather than the attack on the whole country by the Soviets. Notwithstanding that, let’s continue.

In the last six months of 19444 alone, once Lithuania was free of German troops, the Soviets arrested more than 22,000 individuals and carried out over 8,000 anti guerilla actions. The following year they captured 58,000 people.

In this dirty war, some of the Soviets disguised themselves as partisans and went out to commit atrocities. Partisans who were killed were stripped to their underwear and dumped in public places. Soviet propaganda also denounced the partisans as criminals and wartime German collaborators.

In 1953, the Lithuanian underground still managed to kill 84 Soviet functionaries, but by then the area was saturated with police and informants and the partisan war was essentially over,

Prusin points out that the vast majority of functionaries killed by the partisans were Lithuanians themselves, about 21,000 of a total of 25,000 killed, including, 1,000 children. Thus the partisans were trying to prevent collaboration, but failed, and their victims included many innocents.

The whole question of collaboration is thorny in this part of the world. Simply to exist, one likely had to collaborate either with the Germans or the Soviets. There was no other option in this unhappy slice of geography.

Prusin’s view of the partisan war in Lithuania as a civil war is interesting, but it does concern me that it lets the Soviets off the hook. If the Lithuanians were simply fighting one another, I might agree, the the internecine fighting occurred precisely because the Soviets were there. without them, this particular slaughter would not have happened.

I’ll give an overview the rest of Prusin’s history book in my next post when I’ll discuss the broader context for the postwar partisan resistance.

Gossip at my Creative Writing Posts Over at Humber

I’ve been posting on creative writing and gossip about literary events at my Humber School for Writers blog. Come on over and see what I’m up to over there.

Appearances

At the moment, June 2016, I have completed the edits on my forthcoming memoir (May 2017) with ECW Press, The Barefoot Bingo Caller, and I am working hard on rewriting another novel before resuming work on The Rhyming Assassin. There is plenty to do.

This August I will be speaking in Palanga, and then in the fall I’ll be with Humber at Word on the Street in Toronto, The International Festival of Authors, and the Assembly Hall reading series.

Blog Tour Image

Humber Student Paper about Underground

Here’s an article from a student newspaper, the Humber Etcetera, about Underground.

Interview about Underground by Eva Stachniak

Eva is a fine writer who asked some very interesting questions. They will appear in Polish in a Toronto newspaper, and they appear now on her blog.

Associated Writing Programs Conference

See my post about the Associated Writing Programs Conference in Washington.

(This is an association of writing programs whose conference pulls in thousands of writing teachers and students – the last one in Washington in February of 2011 pulled in about six thousand. )

Quill and Quire Article about Creative Writing Instruction

Outtakes From Underground – 2

In this second chapter removed from the novel, Lukas and Monika, their relationship deepening, walk further up the mountain as a storm threatens.

Chapter Seventeen

French Alps, August, 1948

By the following morning, Lukas’s foot, though still tender, could take some weight, so taking a stick for support, Lukas and Monika set out to go a little further along the path that circled the mountain. Their daypacks were light and Lukas felt good to be moving again, however gingerly. The day was bright, but very windy; on the pasture below their hut, the sheep were already grazing, white flecks drifting away from the still figure of the shepherd.

After a while, the path veered sharply up the slope of the mountain in a zigzag. It was harder to walk than Lukas had imagined, especially where the pasture thinned to patches of loose stones underfoot.

The new vista that opened up as they curved around the mountain had many more snow-capped mountains and forested slopes. Lukas had to stop to rest, and they sat on a stone big enough to hold both of them side by side. Monika looked at his face.

“You foot is hurting badly,” she said.

“Does it show?”

“Only if I look hard. You try to be a stoic.”

“What choice do I have?”

“You could tell me about your pain. I wouldn’t mind.”

“It wouldn’t do any good though, would it?”

“It might. Two can bear pain more easily than one.”

Lukas was touched by her words, but he could not linger on the sentiment. To open up his heart would bring on the unbearable memory of what he had left behind.

“I should have waited one more day before going out on the mountain,” he said. “I don’t know how I’ll get back down the incline we just came up.”

They walked on, the going somewhat easier now, but by the time they saw a farmhouse, his foot was throbbing and the high wind was beginning to push together the clouds. The house on the slope was wood and stucco with a tile roof, the animals living under the lower level and the humans up above. A rutted track led away to a pair of houses another kilometer away along the slope.

The farm dogs came bounding out at them, barking and wary, but the dogs did not snap and were called off by a woman at the open door who beckoned them in. It was a working couple’s house, with few ornaments, almost a bachelor’s house, with tools on one end of the kitchen table, newspapers stacked high on a chair, a collection of walking sticks and umbrellas in a stand and the smell of cheese in the air. There was no sign of children.

The farm wife, lean and preoccupied, but otherwise friendly enough, invited them to come in and sit down, watching Lukas limp up the stairs. She made coffee for them and sliced bread and cheese and sat with them for a while at the kitchen table by a window.

Outside, the sky was turning dark. She said she would have to go out to help her husband, who was in a field with the sheep, to bring them in against the storm. But before she did, she asked about Lukas’s foot. She had him remove his shoe and sock. She studied the swollen ankle and made up a poultice, which she wrapped against his skin. Then she finally went out under the darkening sky.

“She’s a kind woman,” said Monika who had grown up in the city and was amazed at the generosity of country people.

“This is how they were in Lithuania too,” said Lukas. “At the beginning, anyway. As the years passed, they became wary of us. They didn’t have much food of their own and the Chekists were terrorizing them. Sometimes, I could only get bread at gun point.”

“And how do you think things will have changed while you were gone?”

“Nothing has gotten better, so they will probably have gotten worse.”

Monika stared into her cup. “Sometimes I’m sorry I put you in touch with the SDECE.”

Lukas looked at her searchingly, but she did not meet his eyes. “If it wasn’t for them, I wouldn’t be in France in the first place and I wouldn’t be here, with you.”

“But if it wasn’t for them, you might be able to live a normal life. A sane life.”

He covered her hands with his, but she still would not look up at him. Outside, the storm was breaking, large, infrequent drops splattering against the panes.

“They don’t seem to be in any hurry to send me back to Lithuania, but if they did, it would be hard for me to go back now. I’ve fallen in love with you.”

She looked up suddenly at this, her eyes alive with hope. “Then don’t go back. Why should you be the one who has to return? Everyone else who got out is looking to America or Australia. Why shouldn’t you?”

“I said I wasn’t eager to go back, but I still have to do it. What about the ones I left behind?”

“It’s their bad luck. And it’s your good luck that we found each other. What were the chances of things turning out like this when I met you in Germany? We’ve had incredible good fortune. Let’s not throw it away.”

“What are you saying?”

“If you do love me, let’s find a life somewhere, maybe in Paris, maybe somewhere else. Leave the SDECE.”

“I just joined! You’re the one who got me in in the first place. And anyway, they seem to move so slowly. At this rate, it’ll be years before they send me back.”

“Or they might send you back tomorrow. You can’t be sure. You need to disentangle yourself.”

“Let’s not talk this way. Do you have any idea how many people died to get me here? There’s a trail of blood all the way across Lithuania and Poland, and what am I supposed to do, just forget about those people and live a private life? The ones I left behind sent me here with a mission.”

Monika shook her head and looked outside.

“Such patriotic talk,” she said bitterly. “Look at where all the European patriotisms have gotten us. Don’t you think that you, personally, have given enough already? Don’t you think there’s an upper limit to what you’re supposed to give?”

“I don’t know. It’s not for me to decide.”

“And what about love? Don’t you believe in love?”

“I do believe in love. I love you so much that I’d marry you, if you’d be willing to take someone like me, even if it’s just for a while.”

“I’d marry you. I’d take you. It’s better to seize some moments of happiness than have none at all.”

The storm was blowing strongly outside, but above it they could hear the bleating of the approaching sheep and then the banging of doors as the pens were opened down below. After a while, the farm wife came in with her husband, and they threw off their oilskin capes. Outside, the rain was pouring down on an angle, borne by the wind. Lukas rose, but the man signaled them to sit, and he and his wife went to a bedroom to change out of their wet clothes.

It was awkward to speak with other people in the house, and each of them sat stunned by the admissions they had made.

“You don’t need to accept my proposal,” Lukas whispered. “I understand that I’m a poor prospect, a kind of condemned man. You’d be a fool to take me.”

“I am a fool, a very great fool, and I will take you,” she whispered.

The farmer was no less lean and no less friendly than his wife, and philosophical as well. As the rain lashed the fields outside and made the window in front of them rattle in the wind, he brought out a bottle of marc de mirabelle, a plum eau de vie, and they sipped their way through it as his wife prepared cheese omelets for each of them.

“Are you Germans?” the man asked over coffee.

“No. Lithuanians,” said Monika. Her French was the better of the two.

“I’ve never heard of such a place. Are you sure you’re not Germans?”

“No. Our country is near Poland. Do you bear a grudge against the Germans?”

“I didn’t lose anyone to the them. I was lucky. But not everyone else has forgiven them.”

“I’ve been in Germany,” said Lukas. “It’s like hell there. No one has any money and the cities are still in ruins. It will take a while before they come here as tourists.”

“I still don’t understand this place you come from. I’ll bring a map.”

He went to the next room and dug around, finally coming back with an Atlas that was fifty years old. When Tomas pointed out where Lithuania was, the farmer clapped him on the shoulder.

“Russians! Why didn’t you say so? You were our allies during the war.”

The rain stopped but the sky did not clear, and the farm wife advised against Lukas’s picking his way back down the mountain in the mist on a swollen foot. Better that her husband should return alone to get their belongings from the hut. He could take them both out by cart the following day to a village where the bus came daily.

“You are engaged, aren’t you?” the wife asked them after her husband had gone out.

“Yes,” said Lukas.

“Then I’ll make you up one bed,” she said.

She was as good as her word. Lukas and Monika slept together that night on a feather mattress with a down blanket, awaking in the dark just before dawn to the sound of the sheep being let out for the day.

“Are you awake?” Monika whispered.

“I am. I was hoping you’d be awake too.”

He reached for her in the cocoon of warmth under the down comforter.They made love in the morning before breakfast, and then rose for the day.

Outtakes From Underground – 1

This is one of two big chapters cut from the last version of my forthcoming novel, Underground. In this chapter, the partisan fighter, Lukas, has become stranded in France, where he went to get help for the movement after the death of his wife, Elena. He has fallen in love with another woman, Monika, a fellow Lithuanian emigre. Two couples are holidaying in the Alps, but even in this peaceful place, Lukas finds violence without and within.

Why was this chapter cut? Editor Janice Zawerbny suggested that is slowed the forward movement of the novel, and I think she was right, so it had to go. Easily a month’s work went into this chapter, but when a section has to go, it has to go.

Chapter Sixteen

French Alps, August 1948

The small bus that took the two couples up the narrow mountain road seemed to lean right over the edge of the cliff before veering around onto the next switchback as it climbed up the mountain. Although the cigarette-lipped driver sounded his horn at every bend, the bus took up most of the road and was guaranteed to knock off any oncoming vehicle or be knocked over the cliff itself.

Lukas was more frightened of the open space at each curve than of anything in his life. Each horn blast was an announcement of imminent calamity as the bus thrust itself out into space.

At one such switchback, a bell sounded back. The driver hit the brakes hard, and the bus came to a stop halfway around the bend. The driver opened the door, stepped outside where he had less than a meter from the edge of the cliff, and threw his cigarette butt into the abyss. He relit a fresh cigarette and walked out in front to where a donkey cart was being led by a farmer with a bell in his free hand.

There was not enough room on the road for the two to pass side by side.

“Who thought this was a good idea?” Lukas asked.

A farm couple sat silently at the back of the small bus, parcels at their feet, and Monika’s sister, Anne, sat across from them with her boyfriend, the French medical student, called Alain. He wore gold-rimmed glasses, which made him look gentle, but his hair was cut very short, like a soldier’s.

“Come on,” said Alain, “you’ve been under fire. This is nothing compared to that.”

But it was much, much worse. The vast, open space was vertiginous: freedom unshaped by any restraint.

“I’ve been under fire,” said Lukas, “but always down in the lowlands where the oxygen is thick. Up here, you can barely breathe and you can see death coming at you from all sides, but can’t do anything about it.”

“The elevation will do you good,” said Alain. “It puts your life in perspective.”

The freedom to travel as a couple was as dizzying as the heights. In the intensely Catholic country where he came from, two unmarried couples could not travel around so easily without the disapproval of onlookers. They would never get hotel rooms. But here in France, anything was possible.

The two drivers out on the road discussed the road impasse over a cigarette, and they agreed that the donkey would go back a hundred metres to where there was a farm lane. The bus driver was grateful and gave the cart driver an extra cigarette to tuck behind his ear.

It had rained in the night and it was still early enough that the gravel road beneath Lukas’s feet smelled of water when he crunched onto it as he stepped off the bus. The last of the morning haze was burning off the mountain meadows exposed to the sun. The driver left them without a word when they did not tip him, and they stood among the six wood and stucco houses of the hamlet, gazing about and wondering how to begin.

Lukas was on holiday and could not quite get used to the idea because holidays had been banished from his life for a very long time. Holidays had caused no problem for anyone else. His handler at the SDECE (author’s note: the French secret service at the time – Service de Documentation Extérieure et de Contre-Espionage), which employed him but which did not pay much attention to him, had assumed he would go on holiday in August like anyone else, even though he had only been working for them for a few weeks.

Alain reached into the side pocket of his knapsack and pulled out some notes, a leather map case, and a fine brass compass with hinged lid that he flipped open as the others stood and took in the surroundings.

The air was very thin, but very fresh, the mountains far cooler than the lowland they had come up from. The view was astonishing for Lukas, who had never seen a mountain peak covered with snow. Not that many were, as the southern alps were somewhat low and close to the sea. Still, the four hikers were above the tree line in the farm pastures, the steep meadows upon which the sheep grazed.

A woman with a scarf over her head and a bucket in one hand came out from behind one of the houses, a longhaired dog at her side. It commenced barking at them, and the sound warmed Lukas, reminding him of the farm dogs in Lithuania. He went to talk to her as he would have back home, and although his French was not very good, he made himself understood. She sold them glasses of milk and a kilo of cheese and so equipped, they started out on their journey, along a track that skirted the mountain just below the village.

In France, people recognized two types of holidays: one was at the seaside and the other was in the mountains. Seasides were expensive because one had to stay in a hotel, but walking mountain tracks was cheap – there were trails and huts and even if the local farmers sold their bread and cheese at inflated prices, the costs were still lower than they were in Paris.

The morning sun was slightly warm on their faces – it would be hot by mid afternoon, but they had not been walking long enough to take off the chill. Lukas had a slight headache brought on by the altitude. That, and the strangeness of walking on and among slopes made him slightly unbalanced. He felt that if he blinked, the horizon might tilt and come up flat, throwing him down to the earth.

One green mountain slope rose directly across from them on their left, a spray of white dots either sheep or mountain goats with no shepherd visible in the distance. The meadow that fell directly beneath them, although green and gentle-looking, sloped at perhaps thirty-five degrees, and anyone who started to roll down the hill might keep rolling until he reached a flatter field hundreds of metres below. There was nothing beyond a couple of large stones along the way to slow such a descent.

Anne and Alain walked ahead, setting a fast, unsustainable pace. Lukas had tramped across a great deal of countryside and knew it was better to conserve one’s strength for the long walk, but he didn’t say anything. It was not so much the walk that interested him anyway, as it was the time spent with Monika. She was radiant beside him, her hair tied down under a scarf and her face slightly flushed.

Lukas was grateful to her. She made a life for him in France when he had no other life to choose from. She was the consolation for his failed mission. No, that was wrong. It made her sound like a poor second. He had not wanted to fail in order to find her, but he never would have done so without his lack of success.

A paradox, then, that didn’t bear too much examination. His heart soared when he was with her.

“I’m surprised your mother let you go on this sort of trip,” said Lukas, finding it slightly difficult to walk and to speak because he was still unaccustomed to the thin air. “We’re like two newlywed couples.”

Anne overheard him and she looked back over her shoulder at Monika. The two shared a smile.

“Am I being provincial again?”

“It’s understandable. Lithuania is a very conservative country,” said Monika.

“Your mother isn’t French.”

“No, but she knows about the realities of life. She doesn’t worry too much about chaperoning us.”

By the time they had stopped for lunch, it was very hot and Lukas took off his sweater and folded it under the straps of his knapsack. They ate bread and sausage and caught their breath. The high spirits of the morning had worn off a little into the first discomforts of travel. Shoes and straps were beginning to chafe, and muscles unaccustomed to exercise to tighten up.

After lunch, they crossed a line of shadow, cast by a neighbouring mountain, like crossing onto the dark side of the moon, and felt the temperature drop suddenly, so much so that they stopped to put their sweaters back on and then increased their pace to stay warm.

As he walked with Monika, Lukas sometimes looked away for a while and then looked at her quickly again to see if he could mimic the delight of seeing her unexpectedly. He found that she was a little like the view of the mountains, a kind of wonderful backdrop that he could forget about for moments, and then be overcome by again when he least expected it.

They walked for two more hours before reaching the eight-bunk hikers’ hut, where they had hoped to spend the night, only to find that it was already full. It was August, after all, and they were not the only students in the mountains. There was another, smaller hut another couple of hours away, or they could sleep outside, but they did not have clothes heavy enough nor rubberized sheets to protect them from the morning mist. Already tired, they pushed on for the sake of the privacy.

It was already very dark on their side of the mountain, although they could see some distant slopes that still had golden light upon them. A quarter moon was rising so it would not be too dark to make their way, but the cold was uncomfortable unless they kept up their pace.

It was hard going. Unaccustomed to the thin air, they were slightly beyond their limit. Monika wanted to rest for a moment, and the other couple went ahead. Lukas and Monika waited for fifteen minutes and then carried on for another hour. When they finally saw their destination ahead of them, night had fallen and the crescent moon was their only light. They could see that a fire was lit down in the mountaineer’s hut, and smoke was rising from a hole in the roof. The hut lay in a dip on the mountainside, and so the path descended toward it.

The slope beyond the edge of the path was very steep at this spot and the track itself was littered with fist-sized stones, and in their descent toward the hut, Monika slipped and fell and began to slide down. She was in danger of slipping onto the meadow, the grass now wet with evening dew, and Lukas lunged for her and ended up falling over her, grasped her sweater and stopped her descent.

“I think I’m all right,” said Monika, though her breathing was fast and he could tell she had been frightened.

“I was afraid you’d disappear down the slope into the night. I didn’t want to lose you.”

He said it so intensely that she looked to his eyes to read his expression, but it was too dark to see well.

“It’s all right,” she reassured him. “I’m fine.” But Lukas had sprained his right foot. The pain was incredible, and once the first wave of it had passed, he began to laugh.

“I’ve never sprained a muscle before,” said Lukas, “in all my years living underground. But out here for a summer’s walk, I manage to hurt myself.”

Monika tucked herself under his right arm and he leaned on her as they hobbled down to the mountaineer’s hut.

The building was small, with a single, wide straw pallet bed on the right, a hearth in the middle of the room with an oil-drum stove missing its door and with three feet of stovepipe and a hole in the roof for the smoke. There were branches and mosses on the left, evidence of one other rough bed.

Once Lukas was inside, his spirits lifted at the heat that was already coming from the fire in the tin box. Anne took half his cheese and promised he wouldn’t be sorry, and she began to cut it up into small pieces that she tossed into pot she had found by the stove. She had Alain pour in some of his brandy and added water to it. Then she cut a loaf of bread into chunks, and very quickly the smell of fresh Gruyere melting in the pot filled the entire hut.

“It smells like old socks,” said Lukas, regretting that he had not been able to buy the less fragrant emmental.

“That’s the trick with cheese,” said Alain. “It smells bad to drive away the uninitiated.”

He may have been right or it may have been Lukas’s intense hunger, but he found the bread on a fork dipped in melted cheese to be the most delicious thing he had eaten in a long time. Anne heated water from a rain barrel for tea, and Alain added brandy to it, as well as sugar, to make a drink that Lukas much preferred to wine, although the others moaned over the lack of it. He had not yet become accustomed to wine. It seemed sour in taste and slow in effect, at least the way they drank it in France. Alain said he would come to prefer wine eventually, but Lukas didn’t really believe it.

The bread and cheese were very good, but they were still hungry, so Anne cut some of their hard sausages into slices and heated them until a little of the fat was rendered, and then she added half a dozen eggs she had been cradling carefully in her knapsack, wrapped in spare socks and handkerchiefs.

This was the moment that they had come for, the sense of accomplishment that came to them after a long day’s walk and the sating of their hunger. It was warm now, and they sat in their shirts with their sweaters over their shoulders. Lukas sat on the bed with his leg stretched out in front of him.

“You should elevate your foot and wrap it tightly in something to keep the swelling down,” said Alain.

“I’ll be fine,” said Lukas. “By tomorrow, I’ll be as good as new.”

They were just beginning to feel sleepy, their stomachs full and their limbs sore, but filled with the warmth of the brandy. A shower of stones rolled down the slope outside the door and a series of indistinct, gruff words sounded. Someone else had almost fallen off the path.

Alain stood up and opened the door, and then stepped out and spoke to someone. Lukas could hear the disappointment in their voices and then the setting down of packs. Alain brought in two men, each dressed in rough, canvas trousers. The older one, around thirty, had thick, dark hair and a green woolen turtleneck sweater unraveling slightly by the right pants pocket. He looked tired and irritated, like someone who had stood in line for a loaf of bread for a very long time, only to find that there was none left for him when his turn came. Alain introduced him as Gerard. The other man was much younger, probably still a teenager, Gerard’s brother, Adrien. They too, had been walking a long time to find a place to stay, and now they were tired and could go no farther.

“I told them they could stay with us,” said Alain, and when he saw the disappointed looks on the faces of the sisters, added, “They have no place else to go and we can squeeze together on one side of the stove to give them some room on the other.”

Lukas was tired as well, but now he rose to the occasion, and Monika offered to make bread and cheese for them and in return, Gerard offered them a drink from his bottle of marc as he and his brother settled on the side of the hut opposite from the others.

“That’s better,” said Gerard. “I was beginning to get cold out there, my teeth all a-chatter. But this stove and the drink and a little food will help me warm up again.”

“We were pretty tired too,” said Lukas.

“I’ve been tired all day,” said Adrien. “We spent last night in the open and we’ve been wandering all over the slopes since dawn.”

“Stayed off the paths?” asked Alain.

“I never take a road if I can help it,” said Gerard, “and I avoid the paths too, if I can. It makes for harder journeys, but more interesting ones.”

“And longer ones,” said Adrien ruefully.

“But worth it,” said Gerard, tapping the younger man on the shoulder affectionately but instructively as well, as if to remind him that he was younger and less experienced. He asked if they minded if he smoked, and when they said it was all right, he took out a pipe and lit it up. “When we wander, we see things you never see if you stick to the tracks – wild goats and shepherds who have been away from people for so long that they’ve pretty much lost the power of speech.”

“And a widow who hadn’t been visited in two years,” Adrien added. “She thought we were ghosts when she laid eyes on us.” He laughed at the memory, but Gerard nudged him and offered him a plate of bread and cheese that Monika had passed to him.

“You must know the mountains well to be wandering off the paths,” said Alain.

“I don’t know them at all,” said Gerard. He passed around his bottle of Marc and a glass, and each person took a drink. “I’m from a small town near Orleans.”

“On holiday?”

“On a holiday from the stupidity of everyday life,” said Adrien, as if repeating a refrain. A couple of strings of cheese hung down from his lips and he reached up to brush them away.

“Ah, so you are vagabonds,” said Alain. He had a slightly academic manner, a need to define that was not judgmental, and so he didn’t sound as if he condescended to the pair.

“You could say that,” aid Gerard. He set down his pipe and began to eat the bread and cheese, scooping it up fast with his fingers. He caught himself with his mouth full and looked at the others watching him, but shrugged without a trace of embarrassment.

“No going back to your old life before the war?” Alain persisted.

“That’s right. That’s exactly it.”

“What did you do before the war?”

“I was a mechanic.”

“Not enough work now?”

“There’s work all right, but nothing like what I had before. I was a mechanic for Grover-Williams.”

Alain whistled.

“Who was that?” asked Anne.

“A French Grand Prix racer. English parents. He escaped to England just ahead of the Nazis, but he came back to join the resistance. The Nazis caught him and executed him,” said Alain.

“But first they put him in a concentration camp at Sachsenhausen,” said Gerard, and he sent the bottle of marc around another time. Lukas was beginning to feel quite drunk.

“That was a bad place,” said Alain.

Gerard laughed. “Don’t I know it. I was there with him, but I survived the death march and here I am.”

“Gerard was different before the war,” said Adrien. “Back then, he wore a chauffeur’s uniform when he wasn’t working under the hood. On his free days, he’d come home and drive me around the countryside and I was the envy of the children.”

“No going back to those days,” said Gerard. He finished his plate of food and relit his pipe. “Some of you have accents. Where are you from?”

“Lithuania,” said Monika.

“That’s odd,” said Gerard.

“What’s odd about it?”

“The Red army liberated me from the Nazis at Sachsenhausen and they liberated your country from the Nazis too. So what are you doing out here in France?”

“The Reds liberated us from the Nazis,” said Anne, “but they didn’t go home after that. Now we have to liberate ourselves from them.”

Gerard shook his head. “If it wasn’t for the Red Army, I’d be dead. And as for an occupying force, the Americans are still in Europe too. I, for one, would prefer the austerity of a worker’s cap to the decadence an American bottle of Coca-Cola.”

An uneasy silence settled on the small hut. They were sitting quite close to one another and the smoke made the place seem closer still.

“Maybe you prefer the austerity of the Reds because you haven’t lived under them,” said Lukas. “Maybe because you haven’t seen all the killing they’ve done.”

Gerard shrugged. “You have to make a choice. Stalin helped us to crush Hitler, and he was the greater evil. Whose side are you on?”

“Neither,” said Lukas.

“Not an option. If you fight Stalin, you’re a fascist.”

Lukas sighed. He had heard variations of this argument before. The very best people, even those who opposed Stalin, sometimes treated Lukas as if he were a war criminal. This was the message the Reds sent to the West, and for all their opposition to the Reds, the West bought this message. It seemed to Lukas that he had a brutal choice: either to be invisible, or to be guilty.

It had been so much easier to fight back in Lithuania, where the enemy was clear. It was hard to know what this man was doing, wandering around the mountains with his brother. Lukas did feel sorry for him. Sachsenhausen, he understood, was one of the particularly bad concentration camps among other bad places, but the very fact that he knew about it showed how well the evil of the Nazis was known. Hardly anyone in France would even be able to find the Komi Republic, the place where thousands of his own people had died in labour camps.

“I’ve never been quite the same since Sachsenhausen.” Said Gerard. “I can’t work a regular job – too restless.”

“And I follow him wherever he goes,” said Adrien.

Made uncomfortable by the conversation, yet unable to part company, Lukas and Alain and the sisters lay impossibly tightly together on the bed that night while Gerard and his younger brother, Adrien, lay on the heaped mosses on the other side of the stove. Lukas took the outside position because his foot still ached from the sprain and he wanted to be able to thrust it out beyond the end of the bed.

Lukas wrapped a piece of firewood with a sweater to soften it and then tucked it under his head as a pillow and put his head on it. With Monika at his side, he fell asleep easily enough due to the alcohol, but he was up again three hours later. The shifting of one of the four of them on the bed made the others shift too, and his foot got bumped. Awakened by Lukas’s sighs, Alain got up in the night and gave him two aspirin tablets and another swallow of brandy, but nevertheless, Lukas’s rest was fitful.

He had lain like this often enough in the past, usually underground, heaped up with others to protect themselves from the Reds. He must have dropped off because he heard a noise, and with a defensive reflex opened his eyes no more than a slit to see what had caused it.

Early morning light was coming in from the hole in the roof. Adrien was sitting with a pack between his knees, going through it quietly, as Gerard sat beside him, watching, his hands in his lap.

Adrien lifted his hand out of the pack to show Alain’s compass in his palm. He flipped open the lid to admire it.

“What are you doing?” Lukas asked quietly, absurdly concerned that his companions might wake up.

“Stealing from war criminals,” said Gerard, and he lifted his hand from his lap to show the blade of a hunting knife.

The glint of light on the blade made Lukas’s mind stop working as it had been doing for months, stop reflecting, stop weighing options. Old reflexes of survival replaced thoughts. He reached behind his head and flung the piece of wood at Gerard, hitting him in the head and stunning him. Adrien looked up, afraid, as Lukas threw himself on the young man, took his throat in his hands and then beat his head rapidly three times against the stone wall of the hut. The boy went limp in his hands.

By now the sudden movement and the grunts that had come out of Lukas’s throat had woken the others, who were rising and shouting in confusion.

“Lukas, what are you doing?” Monika asked, but he had no time to respond, thinking only of the blade that had been in Gerard’s hand. Lukas threw himself on the man as he lay on the floor. Lukas managed to keep Gerard under him with an elbow on the man’s windpipe. He pressed down more and more strongly, did not hear the shouting above him but did hear the croak that came out of Gerard’s mouth.

Lukas rose, finally, pulled the gasping man outside the hut and threw him down over the edge of the path. Gerard tried to raise himself to his knees, but Lukas kicked him in the shoulder and Gerard began to roll and slide down the hill, which was wet with dew. He slid down quite far, over a hundred metres on the wet grass.

Then Lukas went back for the boy, who was conscious, but holding his head in his hands.

“Go on, go after your brother,” said Lukas, and he dragged the boy down and pushed him onto the grass as well. Adrien did not slide, did not move, just sat there. Lukas went into the hut and dug into his own pack, removed a pistol and came back outside. He fired it into the air and Adrien looked up at him, frightened. “Take your sacks and get down there.”

It took a long time for the boy to follow Lukas’s orders. The slope was very slippery and he could not keep upright. He finally sat on the earth and pulled himself down the hill with his heels.

When Lukas turned to face the others, he saw the sisters standing behind Alain, who had picked up a stick. Anne looked terrified and Monika was invisible behind her.

“It’s all right,” said Lukas. “They’re gone now.”

But Alain did not put down the stick and only then did Lukas realize he was holding it to protect himself and the sisters. Lukas wanted to explain, but when the adrenalin from the fight drained away, he crumpled under the weight on his bad foot.

“What were you doing with a pistol in the first place?” asked Anne.

“I’m employed by the French government,” said Lukas. “They issued it to me.”

“Perhaps,” said Alain. “but did you have to bring it along on holiday?”

Monika and Lukas were inside the hut, Lukas reclining on the bed, waiting for the aspirin to take effect and Monika sitting beside him with a gap between them. Anne stood by the open door and Alain stood outside, watching the hill and holding Lukas’s pistol, although it was not entirely clear if his intention was to keep it away from Lukas or to use it in defense against the men.

“In the end, it’s lucky I brought the pistol along, isn’t it?” asked Lukas.

“I wonder,” said Anne.

“Didn’t you see the knife?” asked Lukas.

“No.”

“Alain?”

“I saw something flash, some glint of light. I’d be hard-pressed to say what it was and there’s no knife on the floor now.”

“You were smashing that poor boy’s head against the wall so hard,” said Anne.

“They were going through Alain’s knapsack.”

“They’re vagabonds,” said Anne. “Those type of people live by pilfering. We should have kept our belongings on our side of the hut.”

“I awoke to see a thief and a knife,” said Lukas. “What did you expect me to do?”

“I did not expect you to come this close to committing murder.”

Lukas could not believe his ears. “Alain?” he asked.

The medical student did not turn to face the inside of the hut. “By the sound coming out of Gerard’s throat, a few more seconds and you might have broken his windpipe.”

“Monika?”

She would not look at him. “I was frightened. I thought you had gone out of your mind.”

“But I didn’t go out of my mind.”

“Maybe Anne is right. You went a little out of your mind. There were four of us and two of them. What could they have done?” She looked toward the door. “Where are they now?” she asked Alain.

“They’ve moved along out of my line of sight.”

“What if they come back?” she asked.

“They won’t come back,” said Lukas. “We have the pistol, remember? They’re afraid of us, not the other way around.”

“The question now,” said Alain, “is what we do next.”

“I don’t understand any of you,” said Lukas. “We have driven away a pair of thieves. They aren’t dead. We saw them walk. We should continue on our way as planned.”

“It doesn’t feel like much of a holiday to me any more,” said Anne. “And I don’t want to be wandering around the mountains where those two are.”

“They are afraid of us now,” said Lukas.

“Maybe. Or maybe they have friends.”

“These are unreasonable fears,” said Lukas. “You can’t let them win by giving in like this. We’ve beaten them back.”

“I wonder if we shouldn’t report this to the police,” said Alain. “Remember that story about the widow? I wonder what they might have done at her place if she found them pilfering.”

“Where would you find the police?”

“We’d have to go back to the village we started from and ask there,” said Alain. “Then we could decide what to do next.”

Lukas listened with resignation as their plan developed. He could not go with them in any case because he could not move with his foot in its current state. Anne would not let Alain go on his own in case he ran into the brothers again.

“Monika?” he asked.

She would not look at him. “I shouldn’t leave you alone,” she said. The formulation of words irritated him.

“I have a pistol. I’ll stay outside by day so I can see the surroundings. I’ll stop the door at night. You should go with them. You don’t have any weapons and there’s safety in numbers.”

“I thought you said we had nothing to worry about.”

That was exactly what he thought, but he was not going to say so. He felt on the verge of being betrayed, and he wanted to push the matter. Better to know for certain that he had been betrayed than to have the shadow of it over him.

“I want you to go,” he said. “I’ll follow tomorrow, when my foot has healed.”

“What if it doesn’t heal by tomorrow?”

“Then I’ll go the day after. The air is good for me up here – clear. I need a break from Paris anyway. Go with them. I’ll meet you back at home after a few days. I can see in your eyes that the trip’s been spoiled.”

He could not quite bring himself to apologize for striking the men. That would have been too much. But Monika’s doubt in him made Lukas want to drive her away.

The departure was awkward. The sisters and Alain were careful around him, making sure he had enough food and checking the rain barrel outside for sufficient water. Alain gave him the eight remaining aspirin tablets and half a flask of brandy, and told him the best cure was staying off the foot altogether.

Monika kissed him and embraced him a little too tightly, Lukas thought, and it seemed to him that their spirits lifted as soon as they walked away from him in the direction they had come the day before. Of course, he had no way on knowing for sure what was going through their minds. He might have been imagining it.

In his anger and confusion, Lukas tried to convince himself that he did not mind being alone all that much. He rather enjoyed it, knowing exactly where he stood. His pain was not too bad as long as he kept his foot elevated and put no weight on it.

At mid-day he boiled water for tea and ate some bread and cheese and a little sausage. He put some dried apple rings into his tea and let the mixture cool a little and then ate it as compote. He scanned the slope beneath him from time to time, but did not really believe Gerard and Adrien would return. He had the superior weapon, and if they had had a pistol of their own, they would have had it out right from the first.

Tired from the restless night, he slept in the afternoon, and when he awoke it was late and the sun had moved around the mountain, leaving his hut in shadow.

Toward six, he tossed wood into the opening of the tin stove, heaping a large number of small sticks to get a hot blaze, intending to make tea. The door flew open behind him and his first thought was to reach for his pistol on the bed, but he heard Monika say his name.

She went straight to him and took him in her arms, startling him so he set his weight on both feet and then winced. She sat him on the edge of the bed and kissed him, and then slipped the knapsack off her shoulders. She did not stop there. She took of her sweater and began to take off her shirt.

“The door is still open,” he said.

“I don’t care.”

He was overcome with wonder at the sudden change, and overcome by his sudden need for her as well. During the time he had spent with Monika, the electricity of her touch was very intense, yet he had not identified the fire as desire. How was that possible? It seemed so odd to him now, to have been so disconnected from his own feelings, and he laughed at the rightness of their reaching for one another now, and the foolishness of their having taken so long to do it. He didn’t ask her why she had changed her mind. He didn’t ask her anything.

She undressed and he did the same, but could not remove his pants completely because he couldn’t slip the pant leg over the hurt foot, and even so, after she lay on the blanket he’d put down on the straw pallet, he winced again when he put a little pressure against the foot.

“You lie on your back,” she said, and he did as she said and she lay on her side for a while, her breast pressed against his arm as they kissed. He had not seen so many women undressed up close that he could be indifferent to her, and for a moment he thought of the shape of his dead wife, a little shorter and more compact, the skin ruddier than this pale beauty, and then he forced the comparison out of his mind. He tingled so intensely that he was almost alarmed by the situation – his whole body felt as if it were coming back to life.

“Just lie there,” she said. “Let me do this.”

She made love like a Parisian, a woman who had seen something of the world, and he admired her knowledge and her expertise, her lack of modesty, the characteristic of the countryside he had come from.

When they were done, she kissed him and moved off him to lie at his side and he breathed the smell of her hair, which had something in it of the mountain grass and something of herself – her scent was neither floral nor musk, but almost a taste.

After a little while, they made love again.

Later, she rose and put a few more sticks in the fire, pushed the door more tightly shut and returned to the bed where he pulled a blanket over them. She was cool to the touch at first, and stayed close to him for his warmth.

After some time had passed, he said, “You came back alone.”

“Yes.”

“Where you afraid?”

“I was. Let’s not talk about that. Let’s get dressed and eat something. I’m very hungry.”

Monika went out side to clean up by the rain barrel. She came back in and kissed him once before dressing, and he dressed too. He put sticks on the fire again. Monika had brought concentrated beef tea, which she added to a pot of water, and she cut some sausage into the broth as well as a carrot and an onion. When this soup had boiled for a while, she cut up some of their bread, which was beginning to go stale, lay it in the bowls and spooned the soup onto it and then shaved some cheese on top. She made Lukas wait a little until the cheese had melted. She also took out a bottle from her sack and showed it off to him.

“What’s this?”

“Homemade cassis. I bought it at a house I passed. I love the taste of black currants – they remind me of my summer holidays in the country.”

The cassis liqueur was cloying on its own, but with water, it tasted good – slightly sweet, and as for the aroma, it smelled of home. For Monika it was a taste of the countryside, and for Lukas it was a taste of summer as well, for the black currants ripened in the hottest days and children too young to be much use for anything else were sent out to pick them. Like their spring equivalent, rhubarb, black currants were too sour to be eaten without sweetening, and when Lukas was sent out as a child, he would smuggle a little sugar with him, to be sprinkled over the first currants he picked to sweeten the rest of the labour.

When they had eaten, Monika rinsed out the bowls. They heated water again and made more black currant wine and ate wedges of chocolate for dessert. Putting on their sweaters against the evening chill, they went out to sit on the bench and watch the crescent moon rise in the sky.

“You were afraid of me this morning,” said Lukas.

“But I’m not any more.”

“I see that.”

“There are parts of you I’ll never know. Parts that will flare up, but I think I want you even so, as long as you never get violent toward me.”

“I never hurt my friends. And especially not you. I love you and would do anything to protect you.”

She nodded and didn’t say anything. She didn’t need to. She was pressed into his side.

Very slowly, as the night sky darkened, the specks of stars became brighter.

“Why did you stay behind in Lithuania when the Reds came back?” Monika asked. “You should have known what to expect from the first time around.”

“My father was a farmer, and it’s hard for farmers to leave behind their animals and their land. I stayed out of loyalty to them. Then it was too late.”

“And where did you meet your wife?”

Monika was looking up at the stars as she asked this question, and her face in the pale light gave no indication of what was going through her mind. He didn’t know how much she knew.

“We were in the underground together, just comrades in arms at first.”

“It must have been very hard. You never had a time like this, did you? A time free of worry.”

“No. It wasn’t possible then. We took what we could get and we were grateful for it.”

“Her name was Elena?”

“Yes. Do you resent me for have loved someone before you?”

“No. I’m just glad to have you now. But it’s a terrible world we live in.”

They had all lost someone, and many had lost everything. They were a generation who took it for granted that the past had been very bad and they wanted to go forward from this, to make up for the lost years. It did not do much good to look back when the past was still so close, unless it was in times like this, where two might share a little of what had been lost.

“You had someone before too,” said Lukas.

“Yes.”

“Who was he?”

“Someone I met in Paris, a stateless boy. He joined the legionnaires as soon as Paris was liberated. He was in the French army chasing the last of the Nazis back into Germany, and he was killed near Stuttgart in 1945.”

They sat outside until the moon was very high, and then it became too cold and they went to bed, shivering. They did not make love that night, but clung to one another for comfort against the cold.

Some Good Partisan links on Youtube

Here are three good links among the many of varying quality one can find on YouTube.

The first is a short film about an actual partisan bunker in Northern Lithuania being visited by military types in what appears to be a commemoration.

The second is a trailer from the Lithuanian Film, Vienui Vieni (Utterly Alone), a feature about the partisan resistance.

The third consists of a series of photos with music. The photos consist of some of the classics from that period.

Twilight of the Partisans

While most of the partisan activity in Lithuania was over by 1953, remnants of the movement hid out across the country, with one hundred and forty-two still active in 1954, down to fifty-one in 1955.

One by one they were hunted down, and although individuals survived in hiding into the seventies, the last one shot in action was Antanas Kraujelis on March 17, 1965.

Kraujelis is on one hand a fascinating and tragic lone hero, a romantic hold-over with a lion’s mane of blonde hair, a man who managed to fight on alone long after the battle had been lost. On the other hand he is considered by some to be a murderer for the action he took against civilians.

Which version of the story are we to believe?

Born in 1928, Antanas Kraujelis was the only son of seven surviving children of a working farmer whose income was stretched to feed all the mouths in the family. Although he was good in school, as the only son, Kraujelis was needed to work on the farm.

Since he was of a patriotic nature, he became partisan courier after the war, living aboveground, but armed. The pressure was growing for farmers to join collective farms; local communist activists were coming around frequently to take away food; and the draft into the Soviet army was looming. Under these conditions, Kraujelis went underground in 1947, somewhat after the heyday of resistance.

One of his first acts was to rescue the rotting corpses of a pair of partisans who had been left out in the open to decompose as a message to potential supporters.

The families of partisans suffered for their children’s actions, and the Kraujelis parents and remaining children were deported in cattle cars to Irkutsk in 1951.

By 1952, Kraujelis’s former partisan leader, Bronius Kalytis-Siaubas, had been captured and turned and worked as a “smiter”, seeking out his former comrades to betray them to the KGB, but he never did manage to entrap Kraujelis.

(At this point in the biography of Kraujelis, it occurs to me that his story bears many similarities to the story of the main character in my novel, Underground).

Kraujelis continued to hide out, something of a Robin Hood, sometimes changing into women’s clothes to escape detection, or hiding his long hair in a military hat and dressing in a Soviet uniform to hitch rides in passing military cars. Whenever he stole from warehouses or stores, he left notes explaining that he was acting as a resister against the Soviet occupation. And he was not willing to live unnoticed – he wrote letters to Communist activists, telling them not to betray their country.

He managed to create a whole shadow life, marrying Janina Petronis and having a son with her, all the while living in a secret compartment under the fireplace of a house.

Kraujelis’s parents and family returned from Irkustk in 1959, but they were given no peace in Lithuania and his father was deported to Siberia again in 1960.

In March of 1965, Kraujelis’s place of hiding was discovered in an operation run by the infamous Nachman Dushanski, who had had a hand in the torture and execution of another famous partisan, Adolfas Ramanauskas. Sadly, the secret compartment was opened by the owner of the house, Pinkevicius, who was wounded when Kraujelis fired (Pinkevicius went on to die of his wounds).

Under gunfire, the KGB operatives fled the house. Left behind inside, Kraujelis burned documents and defended himself by firing from the windows and throwing a grenade (which did not explode). His wife, Janina, was given a letter, asking him to give himself up, but when she delivered the note to him, Kraujelis said he would not be taken alive. He bid farewell to his wife, went upstairs and shot himself.

His wife, Janina, was charged with supporting a partisan and spent four years in jail while their son was put into an orphanage. She recovered the son four years later.

Kraujelis’s father lived to see a memorial raised to his son in September of 1999. He visited as well the yard of the house he and his family had lived in during better times. The house had been bulldozed by the collective farm, but the stones of the foundation were still visible. The apple trees father and son had planted still stood as well, their branches heavy with fruit.

Now square the story above with the story on a Lithuanian web site with the headline: Lithuania Honours Partisan who Murdered 11 Civilians:

The article attacks Kraujelis’s actions up to 1952, when he killed various people, but at least one of the commentators mentions that Kraujelis was firing back at Communist activists who were firing at him.

This is the sort of split one sees often on this subject in Lithuania. The children of those executed by the partisans remember them as murderous bandits. However, sometimes they do not mention that the executed persons were carrying out the instructions of the Soviets.

I hesitate to use the word “collaborators” in this context because as Tony Judt has pointed out in Postwar (p.33), the simple notion of collaborator does not really apply to the East. Still, the people killed by Kraujelis were enemies, he perceived, of Lithuanian independence.

Such a moral mess. I hesitate to judge any of these people because I sit in a comfortable time and place. As Timothy Snyder has pointed out in his Bloodlands, we should really spend time considering the humanity of all those involved.

The Partisans Seize Merkine on December 15, 1945

Sixty-five years ago, on December 15, 1945, the Lithuanian town of Merkine was seized by a force or partisans and held for a day before being abandoned – the partisans had wanted to thumb their noses at the ruling Communists and paid for the action with the loss of five lives.

The action was described in detail by Adolfas Ramanauskas, code-named Vanagas, in his memoir Daugel Krito Sunu. In that book, written four years after the event, Ramanauskas named forty other partisans of the 200 who participated, and said he was the only one still left alive. Ramanauskas himself was betrayed in 1956, imprisoned and tortured and executed in 1957.

Lithuania is a small country with fewer degrees of separation than larger places, so I wasn’t entirely surprised to find a slight family connection. Ramanauskas had worked in the Alytus teachers’ college, where my mother was the director during the war. In the Alytus museum devoted to Ramanauskas, there is a photo of him standing behind her – she would go on to flee to Canada to raise three sons. He would fight in the forests and die.

Ramanauskas’s detailed description of this battle was the inspiration for one of the more important chapters in my novel. The battle is used in my book to show the high point of partisan strength and optimism, a peak from which the decline began quickly and continued until most of the partisans were killed or captured by the early fifties.

Merkine itself is a ghostly sort of town, a place that has fascinated me since I first visited it in the late eighties to hear the story of a priest who had been an agent for the KGB. Even then, the town seemed slightly behind the times, a place of sandy streets, picket fences, and dogs barking at sunset.

And much is very sad about the place, a hill at the confluence of the Merkys and Nemunas rivers that has been a defensive position frequently attacked, burned, and bombed over the centuries.

The hill has been inhabited for over ten thousand years, its fort burned by the Teutonic Knights in 1377. It received the right to rule itself as a city at about the same time as Vilnius, in 1387. King Vladislovas Vaza died there in 1648.

The city was burned in 1794, 1803, and 1822. The place was bombed during WW1. Over the centuries, Jews formed an important part of the town, the majority of the inhabitants at the centre. There were 3 synagogues and 145 stores, most of which belonged to Jews.

The centre of the city was bombed by the Germans in 1941 and about three thousand Jews murdered there (one Jewish source says 1,600) largely by Lithuanians.

I go to this town from time to time, once to visit my friends, the Jurasai, who have a house that overlooks the oxbow where the rivers meet. When the mist rises up at sunset, you can imagine all too well what the place must have been like a thousand years ago.

As I mentioned in one of my earlier posts, the church had a machine gun nest in the tower when Ramanauskas and his band attacked. The old Orthodox church, built by czarist authorities on the foundation of the burned city hall, is now a museum. Two medieval stone posts stand out in the fields, markers of the old town limits. Beyond the town are a German military cemetery, a Red Army monument, a monument to Soviet Partisans, and a monument to Lithuanian partisans.

This place seemed to represent best what Simon Schama said about the area in his book, Landscape and Memory:

There was, I knew, blood beneath the verdure and tombs in the deep glades of oak and fir. The fields and forests and rivers had seen war and terror, elation and desperation; death and resurrection; Lithuanian kings and Teutonic knights, partisans and Jews; Nazi Gestapo and Stalinist NKVD. It is a haunted land where greatcoat buttons from six generations of fallen soldiers can be discovered lying amidst the woodland ferns.

Such a melancholy site! But it keeps drawing me back. I’ll go there the next chance I get. It is a site that might be called the same as historian Timothy Snyder’s new book – Bloodlands.

My Dinners with Joe and Wayson

Joe Kertes, Wayson Choy and I were all English teachers at Humber College in the eighties and the nineties, often teaching remedial English or ESL, and living the lives of communications teachers everywhere – which meant hundreds of papers to mark at mid-terms an end-of-terms, and then blessed relief over the summer.

We were all somewhat literary – I was working on the side with Descant , a Canadian literary journal and Wayson was involved with theatres. Joe Kertes published first in 1988, probably the first Humber College teacher to publish anywhere, and went on to win the Leacock Medal for Humour. He then started the Humber School for Writers and published adult and YA books. I published next in 1994, a novel called Dinner at the End of the World. Wayson, the oldest of us, published last, in 1995. I remember saying to him to enjoy the moment because publishing glory did not last – that book, The Jade Peony, has gone through around 30 printings, sold tens of thousands of copies, and been adopted in classrooms across the country.

Since then we have all published to greater or lesser acclaim, depending on the book, and I now run the writing school Joe started while he has gone up to be dean and Wayson has retired to devote more time to writing.

The one constant has been our dinners, usually at the Pearl Court Restaurant over on Gerard near Broadview. We meet there every couple of months to overeat and talk about the college and literature and who is doing what.

These dinners have been a refuge and a consolation over the years – gratifying to begin again after Wayson’s heart attacks (twice!), after one of my manuscripts went bust, after various types of turmoil at home or at work. During the summer writing workshop, we’ll have a big crowd there – the late Paul Quarrington, Guy Vanderhaeghe, Alistair MacLeod, Kim Moritsugu, Isabel Huggan and others.

But usually it’s the three of us, talking about what we have read or where we are in our books. Wayson is always throwing out old versions, discovering the key to his new book practically every time we meet. Joe and I soldier on as time permits due to our day jobs. We gossip about writers we know and the books they are writing. I suspect we never reach the intensity of My Dinner with Andre, but on the other hand, we have never had a dull moment. After we’ve paid the bill, we’re often still at the table an hour later.

Wayson goes in for minor surgery on December 21, 2010. No big deal. We talked less about that than my own new novel, Underground, out in March next year. Joe told some funny stories about Russell Peters, who received an honorary degree from the college.

But I think of another writer friend of ours, Bruce Jay Friedman of New York. He’s sweet and smart and funny and he has great stories to tell of his lifetime of lunches with his two friends, Mario Puzo, who went on to write the Godfather novels, and Joseph Heller, who wrote Catch-22.

Bruce is the last one left of them.

Wayson, Joe, and I are not quite at death’s door yet. On the other hand, who knows? We’ve had a lifelong conversation that included literature, among other interests. It’s been very good. I hope it goes on for a long time.

New revelations about the brutality of the partisan war come from a book recently published in Polish.

(Summarized from a Lietuvos Rytas Article by Eldoradas Butrimas , November 13, 2011)

“If a child is taught from the cradle to fight indiscriminately for its homeland, that child will grow up to kill anyone who is a foreigner or anyone who disagrees with him.”

This is part of the confession of the late Stefan Dąmbski, a former Polish partisan executioner and a member of the “Armia Krajowa”. He remained so guilt-ridden by what he had done during the war that he committed suicide in Miami seventeen years go.

Apparently, much of Poland has been polarized by the revelations in Dąmbski’s memoir, called “Executioner”.

Dąmbski said of himself: “I was worse than the cruelest beast. I was a typical AK soldier mired in the filth, but they called me a hero and decorated me with a medal after the war – a cross for courage. “

Dąmbski wanted his story to be a cautionary tale for others, but he doubted the book would ever be published.

The former guerrilla said he thought he became such a beast thanks to the patriotic fervor he was filled with in his childhood by his family, his church, and his country.

Born in 1926, he was raised by relatives after his mother died and his father emigrated to Columbia, and he joined the AK as a courier in 1942. When he was told to avoid a former classmate who was collaborating with the Nazis and was slated for execution, he offered to do the job himself.

The next day, Dąmbski invited the classmate into his house, got him drunk, and took him out into the woods where he shot him. He went on to execute over 300 Germans, Ukrainians and Poles, including men, women, and children.

He brutality was extreme. In 1944, despite being instructed by the AK leadership to be friendly to Soviet soldiers, he killed a drunk Russian soldier who was sleeping in a ditch by driving a nail into his head and then riding away on a bicycle.

Similarly, he was instructed not to shoot German prisoners of war, but when peasants turned over a German whom they had stripped naked, he thought it would be too much trouble to look for clothes and shot him instead.

The story being told above is not exactly as uplifting as the stories I used to write Underground, but I think it’s important to lay bare as much as possible in the service of truth, insofar as you can. Sometimes it’s hard to tell who’s in the right, but you need to keep on weighing the evidence.

An acquaintance in Lithuania tells the story of his grandfather, seized during a postwar rural festival and executed in front of his family. This is a real tragedy, a terrific trauma. But the man, it turns out, had been warned not to cooperate with the Soviets in the countryside. Yet he did, and suffered the consequences.

Was this a justified execution, or an example of a farmer caught between a rock and a hard place?

Bloodlands Continued

“By the end of the war, half the population of Belarus had either been killed or moved.” (Snyder, 251).

One of Timothy Snyder’s most important points is that the destruction of civilian populations was not limited to the holocaust (horrifying though those numbers were). Civilian death in the “Bloodlands” of Belarus, Poland, the Baltics and Ukraine totaled about 14 million, these quite apart from military deaths (but including 5.4 million holocaust deaths).

And the worst place of all to be was Belarus, where it was a matter of chance whether one was dragooned by Nazis or Soviets, a matter of chance whether one’s wife and children were killed by Nazis or Soviet partisans.

But suffering was extreme throughout this region, although different for Jews and non-Jews. When the Soviets returned to Poland as they beat back the Germans, they came as questionable allies to the Poles who had already suffered under them. Surviving Jews could only the see the Red Army as liberators.

The Soviets always underlined that the suffering had been Russian suffering, but the fact of the matter was that the Russian heartland was mostly untouched. Byelorussians, Poles, Baltics, etc. bore the brunt. And it was in the interests of the Soviets to underplay the holocaust.

The Soviets also claimed that the war had started in 1941, not 1939. Thus the territories they occupied in 1939, the Baltics, Eastern Poland and Western Ukraine, were considered always to have been Soviet rather than, as Snyder says, “Booty” of an earlier aggression.

German and Soviet occupation together was worse than German occupation alone.

Snyder reminds us that the majority of dead did not die in concentration camps. The majority were shot, starved to death, or killed on arrival at death camps. He reminds us that the Soviet prisoners of war were starved to death until they became useful as labour, but millions had died before this. As well, Germany planned to starve to death another thirty million people in the Bloodlands, but their plans were stymied by Soviet resistance.

I found this whole semi-forgotten plan of starvation freshly horrifying.

As well, I found it horrifying that the Nazi holocaust death machine only really got rolling once it was clear the Soviets could not be beaten quickly, if at all. For the Nazis, victory was claimed in the killing of the Jews as a stand-in for victory over the Soviets.

There is much more in Snyder than I am summarizing here. I’d just like to add two points which are important.

First, the whole notion of the word “genocide” that I have considered in earlier posts is, according to Snyder, a red herring. It is distracting and unnecessary to fuss over definitions of it (although Naimark devotes a book-length essay to the topic).