While I had intended to begin this season with an entry about Robert Heingartner and the shape of my novel in progress, I stumbled across some more partisan biographies while I was in Lithuania last summer and found them too good to remain unremarked upon.

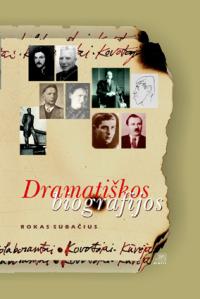

The four come from a book by Rokas Subačius called (in translation) Dramatic Biographies, detailing the lives of twenty-six Lithuanians during periods of first independence and three brutal occupations.

In a radio interview with Shelagh Rogers on CBC radio this fall, I said I keep going back to Lithuanian sources because the place has life stories with very high stakes.

Some of the four biographies provided source material for Underground.

The first life described is that of Juozas Vitkus, code-named Kazimieraitis, who was the head of the partisan region of southern Lithuania. Although he did not write about his own life, he was described in detail by Adolfas Ramanauskas, code-named Vanagas, whose biography inspired parts of Underground.

Before WW 1, Juozas Vitkus should have emigrated as a child to America where his father had gone to find work, but his mother became sick on the way and was held back in London and the children were sent to an orphanage. His father returned from America to round them all up and then went back to farm modestly in Lithuania instead of going on to the USA.

Delayed by the war, Vitkus entered high school in 1919 at the age of eighteen. Lithuania’s independence battles were still going on, and he joined the army and was trained as an officer, serving as a lieutenant in battles with the Poles. He trained as a military engineer in Belgium and visited the Paris World’s Fair of 1937. He was a lieutenant-colonel by 1940 during the first Soviet occupation, but was not deported to Siberia like so many officers at that time.

During the German occupation, unwilling to work in an army subservient to the Nazis, he went into civilian life, meanwhile helping to create the LLA, an underground military school in the resistance.

When the threat of Soviet return became real, the retreating Germans agreed to train and arm about a hundred potential underground resisters. While biographer Subacius does not go into detail on this point, one can see where the story of underground fighters as Nazi sympathizers arises. Some took training and weapons from the Germans (and some were undoubtedly collaborators). However, the majority of partisans, as we know, were simply young men, mostly from rural backgrounds, fearful of the returning Soviets and unwilling to join their army.

Vitkus could not easily withdraw before the approaching Soviets because he had five young children. But after their second arrival (the first was in 1940), he found it difficult to find work under the occupation itself because no one would give a former army officer a job. He finally found work in the remote southern countryside as a bookkeeper, apparently intending to stay legal but out of the spotlight and thus less liable to deportation from a provincial village.

However, the partisan resistance as forming around him, and he could see the lack of military training in these informal groups. Most of the higher officers had fled Lithuania or been imprisoned, and Vitkus joined the partisans with the intention of raising their military training. He was the highest ranking officer from the formerly independent army in the partisan movement.

At this moment it is worth standing back from the life for a moment and watching how history played havoc with the best-laid plans. Vitkus, who chose the code-name Kazimieraitis, had no intention of resisting at first, but he felt compelled to do something for the partisans in spite of the fact that his actions put his family and himself at risk.

One of his first tasks was to organize the resistance and to enforce discipline, in particular on some of the criminals who drifted into the partisan movement in the early days. At least seven of them received death sentences for excessive violence in the resistance.

Vitkus’s bunker was at the confluence of two small streams that did not freeze over the winter, and the only way to reach the bunker door without leaving footprints was to wade in the shallow waters with rubber boots on the way.

Vitkus met with Juozas Deksnys, a partisan stationed in Stockholm who came back into Lithuania to check out the local situation. With him, he hoped to set up ties to the international community and to get help for the resistance.

Vitkus also helped organize the seizure of the town of Merkine, dramatized in my novel. The intention was to assassinate local collaborators. In that action two hundred partisans attacked the town with great initial success, but significant losses as well. By 1948, incidentally, the 47 whose names Ramanauskas could remember were all dead.

Even in 1946, the noose was tightening. After the Merkine action, a captured partisan was tortured until he revealed Vitkus’s bunker. Although Vitkus was not caught, two other partisans were killed and their documents discovered, including Vitkus’s diary and a list of sixty supporters, who were subsequently arrested.

The partisans fought on, but the losses were great. Through 1945 through June of 1946, Vitkus lost 250 shot, 236 arrested, and 213 partisans who opted to take amnesty. Only 300 were left in his area.

After a massive partisan execution action against spies, the resulting MGB combing of the forests stumbled across Vitkus while he was washing his clothes by a stream. He defended himself with a pistol, wounding two soldiers, but was wounded in turn by a grenade and taken alive. The MGB did not know who they had. They beat him during interrogation, but he died of his wounds without giving out any information.

His body was dumped in the marketplace in village of Leipalingis and left there until the MGB discovered who they had killed. Then the body was taken away and buried in a place that remains unknown to this day.

When I was in Merkine again this summer, I visited the partisan monument where he and dozens of other fighters are commemorated. It lies very close to another monument to red partisans and Red Army soldiers, as well as the site of a holocaust massacre.

Underground is dedicated not only to men like Vitkus, but to all the others who died in the forests as well.