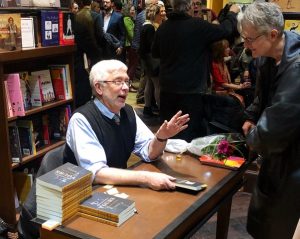

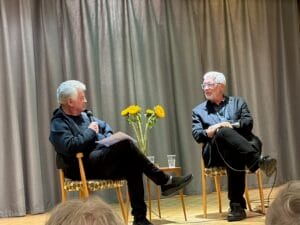

Above – in conversation with Wodek Szemberg at the October 28, 2025 launch of my latest novel, The Seaside Café Metropolis and below a long shot of the audience.

Here are 3 reviews of the novel:

1)

About / Recently Read / Definitely Thriving

November 14, 2025

The Seaside Cafe Metropolis, by Antanas Sileika

“How is it possible to live under tyranny? One must create a sort of fantasy world to shield at least part of oneself from the oppression. And under this shield, people can make alternative lives for themselves, real or imaginary ones.”

There is no seaside at the Seaside Cafe Metropolis, and there is no metropolis either, instead Khrushchev-era Vilnius, Lithuania, to which Toronto-born Emmett Argentine has followed his idealistic socialist mother and still can’t seem to be unravelled from her apron strings, never mind that he’s the one in the kitchen now, or at least overseeing the kitchen, and the rest of his restaurant, the Seaside Cafe Metropolis, which is indeed a cafe, if nothing else. And also the centre of Bohemian life in Vilnius, although there isn’t much competition for that distinction, and Antanas Sileika’s The Seaside Cafe Metropolis is a rich, funny, and quietly poignant chronicle of this most distinguished undistinguished establishment, where KGB agents listen from the basement to microphones installed at the tables so that nobody can ever say in so many words just how much the Soviet reality has failed to lived up to its promise, but also everybody knows, so nobody has to. And in the meantime, Argentine (not in fact from Argentina) contends with informants trolling for dissidents, securing a jazz band, the mediocrity of Soviet champagne, the dramas of his young patrons (the poet, the philosopher, the sculptor, the artist), a visit from Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir, protecting his employees from the terror of the state, and a one unforgettable chain of tragedies involving a lion, each chapter complete with a recipe (“Buckwheat Groats,” “Potato Kugel,” “Herring and Onion on Warm Potatoes”) rounding out this culinary experience, which turns out to be a celebration of community, solidarity, and the transformative power of imagination.

2)

The Seaside Café Metropolis by Antanas Sileika

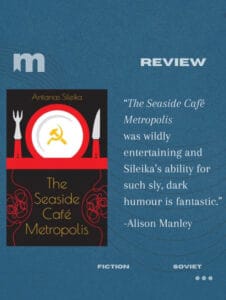

Miramishi Reader – November 16, 2025 by Alison Manley

There’s a certain wry tone in Soviet comic fiction — sly, humorous, incredibly bleak, resigned, and also still managing to delight in the absolute absurdity of it all. It’s very specific, and if you’ve read any Soviet writers, you’ll know what I mean. This is the tone of The Seaside Café Metropolisby Antanas Sileika – a book published in 2025, but managing to capture the tone of Soviet fiction from these few decades after the formal end of the Soviet Union.

Set in Lithuania in the late 1950s and early 1960s, Emmet Argentine is the son of a Canadian woman who decided to commit to her ideals and go live in Vilnius, the capital of the Lithuanian Soviet Socialist Republic, part of the USSR and still resistant to rule from Russia. Emmet, a trained chef who worked in the top hotels in Toronto, he finds himself an oddity in Vilnius. Useful to the regime, he’s allowed some freedoms, but also toes the line, keeping himself, his mother, and his staff safe. When he’s assigned to run a new café, modelled on the things that people might want from the West, he embraces it, even though the Seaside Café Metropolis is none of the things the name claims it is.

This novel reads more like a collection of connected short stories: each chapter is a self-contained tale about Emmet, the café, and the cast of characters who haunt the place. Each story is shaped around a meal – usually Emmet’s attempts to make something that appeals to Lithuanian tastebuds, reflects the limited ingredients he can get his hands on in the country, and also characterizes the kind of bohemian café he wants to run. Each chapter ends with a recipe for the central dish, usually with some commentary thrown in about how it had to actually be made in Lithuania.

This novel was so darkly hilarious that I spent the whole time reading it and chuckling. It was wildly entertaining and Sileika’s ability for such sly, dark humour is fantastic. Sometimes we need to laugh, and sometimes we need to laugh with a shadowy hint for a shadowy moment. This book is perfect for that latter need.

Details:

Antanas Sileika is a Canadian author of six previous books of fiction, as well as two memoirs. His collection of short stories, Buying on Time, was shortlisted for the Leacock Medal for Humour and the Toronto Book Award, and longlisted for CBC’s Canada Reads in 2016. His books have repeatedly received starred reviews from Quill & Quire and have been listed among the one hundred best books of the year in The Globe and Mail. One of his novels, Provisionally Yours, was adapted into both a feature film and a television serial in Europe. He currently lives in Toronto, Ontario.

Publisher: Cormorant Books (September 27, 2025)

Paperback 8″ x 6″ | 294 pages

ISBN: 9781770868106

3)

The Seaside Cafe Metropolis, by Antanas Sileika

Cormorant Books

There is no seaside at the The Seaside Cafe Metropolis, and there is no metropolis either, instead Khrushchev-era Vilnius, Lithuania, to which Toronto-born Emmett Argentine has followed his idealistic socialist mother and still can’t seem to be unravelled from her apron strings, never mind that he’s the one in the kitchen now, or at least overseeing the kitchen, and the rest of his restaurant, the Seaside Cafe Metropolis, which is indeed a cafe, if nothing else. And also the centre of Bohemian life in Vilnius, although there isn’t much competition for that distinction, and Antanas Sileika’s The Seaside Cafe Metropolis is a rich, funny, and quietly poignant chronicle of this most distinguished undistinguished establishment, where KGB agents listen from the basement to microphones installed at the tables so that nobody can ever say in so many words just how much the Soviet reality has failed to lived up to its promise, but also everybody knows, so nobody has to.

And in the meantime, Argentine (not in fact from Argentina) contends with informants trolling for dissidents, securing a jazz band, the mediocrity of Soviet champagne, the dramas of his young patrons (the poet, the philosopher, the sculptor, the artist), a visit from Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir, protecting his employees from the terror of the state, and a one unforgettable chain of tragedies involving a lion, each chapter complete with a recipe (“Buckwheat Groats,” “Potato Kugel,” “Herring and Onion on Warm Potatoes”) rounding out this culinary experience, which turns out to be a celebration of community, solidarity, and the transformative power of imagination.