The interview was published in translation in Italy in December of 2023. Here are the questions and answers in the original English version:

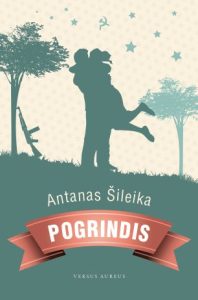

- The title of the novel, ‘Underground,’ is quite evocative, especially considering your exploration of the underground resistance of the Lithuanian partisans against the Soviet occupation. What inspired you to delve into this often overlooked part of history?

For many decades, in North Americas the story of the second world war focused on the fight against Nazi Germany on the western side of Europe, and to a certain extent North Africa. I grew up with films and television programs about Americans in combat, Britain under the Blitz, the Canadians in the Netherlands and in Italy, especially at Monte Casino, as well as stories of French resistance. These were scenes from the story of a more or less “good war” that ended in May of 1945. What happened in the east, in the territory historian Timothy Snyder called “Bloodlands”, places occupied first by the Soviets, then the Germans, and then the Soviets again, cannot be called simply a “good war.” It was far more complicated than that, with massive repression against civilian populations yet simultaneously the liberation of what remained of Europe’s Jews. And the war continued there, underground, for over another half dozen years until local armed resistance was crushed. I knew about this story for all of my adult life, and I knew about the partisan resistance as well but I needed to reach a point in my writing life where I felt I could manage to tell this story, and I needed to wait for a time in history when the story could be received in the west. For a long time, the story of the long war in the east without a “happy” ending, was of little interest in the west. But that has changed, and more recently interest has been amplified since the war between Russia and Ukraine. The zeitgeist now permits us to look again at the stories that were not told in the past.

- Rather than focusing on grand historical narratives, your novel delves into the story of a small country caught between two superpowers, Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union, during WWII. You chose to portray this through the perspective of partisans who, despite being heroes, are primarily ordinary individuals. While your Lithuanian heritage likely influenced the setting, how significant is it to adopt the viewpoint of smaller nations and everyday people in accurately depicting the brutal impact of power and violence?”

There is a kind of Great Power provincialism that believes important places are New York, London, Paris, etc. and their outlying provinces. Every beach is vast, but the universe is contained in every grain of sand on that beach, so I go looking for universal humanity in that tiny grain of sand. The smaller the stage, the greater the drama. The story of war is on one hand grand, but on the other hand very personal; on one hand perpetually unchanging in history as men go to war and women weep, and on the other hand particular in different places. The detail of a particular place and time awakens in me awareness of the deeper universality of the human condition. If the purpose of literature is to make fresh the human condition, for example to tell a love story that is familiar and yet new, then my attempt is a version of this too, to show big events on a small stage, what it’s like to lie, for example, between the hammer of wartime Germany and the anvil of the Soviet Union.

- At the conclusion of the novel, the main character Lukas, residing in Canada and sharing similarities with your own biography, receives a letter from Lithuania, prompting him to retrace the threads of his story—the narrative depicted in the novel. To what extent do the character and the novel draw from autobiographical elements?”

My novel set in Lithuania is a form of imaginary autobiography. My eldest brother was born in Lithuania in 1943. When my parents fled in 1944, they thought they were departing for a short time and would have left my brother behind if his grandmother had not been away. Many other parents did this, and ended up with children left behind, children who could not get out of the Soviet Union for many, many years. My second brother was born in Germany and I was born in Canada. What would it have been like for me to meet my eldest brother decades later if he had been left behind in Lithuania? Would he resent my relative richness and freedom in the west, or would he be eager see if our shared blood brought us together? Or, alternatively, what would have happened to me if I had been there? One of my uncles lost all his teeth to Soviet interrogators in 1940, and another died in the gulag in 1955 for the crime of having been a successful farmer. One of my cousins was terrorized his entire life because he had relatives abroad. These are lives I did not live, but they are lives I can imagine and I have written about them.

- The novel extensively relies on deep archival research, yet in one of its initial chapters, characters Lukas and Rimantas destroy an archive containing their student records. Does this juxtaposition suggest an ambiguity in your relationship with memory? Moreover, does the narrative imply an inherent ambiguity within memory itself?

Memory is a mixed blessing. In the Soviet period the past was a dangerous place. A brother living abroad, an article one might have written in a student newspaper, clothes that betrayed previous bourgeois habits, a father deported to the gulag – any of these could imperil you. Young women whose parents or previous husbands shared “suspicious” last names were in a hurry to get married in order to get new last names, to disguise the past. As the Soviet Union collapsed, these various secrets were uncovered in a burst of exhilaration. But not all of them. There were guilty secrets too, of collaboration with one regime or another, with crimes in the Holocaust and other circumstances. Now, we have moved from simply hiding secrets, or simply revealing them, to look for nuance where in the past we saw only heroes and villains. But the past remains a dangerous place, if only because a writer like me can get stuck in one of the eddies in the current of history, obsessing on actions that cannot be changed. Also, I find an exasperating tendency in people to do one of two things: know little or nothing of the past yet have an opinion about it, often based on simplistic movies or TV shows, or simply condemn the past as if it were stupid and ignorant because we know more than people did in the past and we are more virtuous than those who lived in the past. But if the past is always guilty, we in the present will soon be guilty too, probably for crimes we didn’t think of, such as wearing clothes or electronic devices made by repressed people or children.

- Beyond its historical context, the main theme of the book revolves around a love story. Love has the power to unite, separate, save, and endanger. How significant, in your opinion, is the importance of this emotion in human experiences, both on an individual level and within collective contexts?

One of my other novels is called “Provisionally Yours”, a kind of joke on the phrases such as “Your Truly” or “Yours Forever”. Is this a cynical evaluation of romantic love? I don’t think so. I know the story of a man who built a kind of altar in his Canadian home in honour of the wife and daughter he left behind when he fled Lithuania. His love was steadfast and permanent. On the other hand, my aunt married a man in Canada who “forgot” to tell her he had another wife in Lithuania who was still alive. His love was temporary. The characters in my novels feel the pressure of history upon them in a manner more pronounced than in North American stories where characters have greater agency. I would like to think that romantic love is strong enough to withstand the pressure of cataclysmic world events, but I am afraid I cherish this thought more as hope than as a certainty. Another kind love, one for place or tradition, is considered a bit old-fashioned now, even suspicious, but this love for home or country, childhood time or family tradition is very strong in me and in others, but too often now dismissed as nostalgic or nationalistic.

- In the initial sections of the novel, Lithuanian partisans hold firm belief in assistance from the Americans and Western nations, yet this hope gradually diminishes. Lukas, too, discovers no promised refuge in France and Canada. Does the novel not only condemn Soviet oppression but also critique the Western world for its reconciliation with the USSR?

I understand that among Poles there is something known as “The Great Betrayal” by the western powers, who went to war because of the invasion of Poland and then declined to finish the job they had started. Lithuanians and the Baltics “felt” western to themselves, and these places were considered “almost western” by Russia and other regions in the Soviet period. The Baltics adhered to an idea of the west as a place of rule of law, of liberal values, whereas the Soviet Union represented tyranny and lies. So yes, people who feel they “belong” to the west will wonder why they have not been granted membership to the club. But this desire to be western has to take into account the cost it would have required for western powers to continue the war. Even now, we seem to be entering a period when the cost of the war in Ukraine seems too high to some Americans and others. I suspect that Ukraine too “feels” itself to belong to the west, and hopes to be helped to become more so while fighting a tyrannical east. It is interesting to me that people in Poland and the Baltics and other places do not even want to be referred to as “East Europeans” because this title is somehow demeaning.

- The novel was initially published in 2011, well before the onset of the war in Ukraine. In light of the events unfolding over the past two years, has the narrative taken on new or altered significance for you?

Some historical tendencies seem to be true over time, but then get forgotten. After the collapse of the Soviet Union, Baltics and Poles remained wary of Russia, which has historically been expansionist, a colonial power exerting itself over nearby countries and territories. Generally speaking, western powers and intellectuals imagined that particular historical remnant of Russia’s foreign relations had passed. Then came wars in Chechnya, and Georgia, but those places seemed so far way. Even the invasion of Crimea seemed somehow unimportant. Eastern European nations rang alarm bells, but European Union members still did not see the threat from Russia as real. Then came the invasion and war in Ukraine. In Lithuania, members of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs tell me western European politicians and government functionaries now say, “You easterners were right all along”. I have noticed a tendency not to take easterners seriously even among my friends, who thought of me as a “typical” East European obsessed with Russia and Putin. It is only after Finland and Sweden recognized the threat of Russia and joined NATO that my friends began to nod their heads. In other words, some westerners only take other westerners seriously. It’s a little frustrating. Even now, I see traces of a sort of double standard as regards the actions of East Europeans. When Belarus, in the pocket of Russia, flies in migrants from Syria and Libya and then escorts them to the Polish and Lithuanian borders in an effort to wage a hybrid sort of war, I read in western newspapers that these poor unfortunate migrants lured in by Belarus should be treated more kindly by Lithuania an Poland. It’s as if the Baltics and Poles are at fault for the actions of Belarus. Interestingly, I have not heard the same response since Finland closed its border with Russia after the same sort of thing happened there.

- Vincentas, Lukas’ brother, turns to religion as a means to resist the atheist invader in the narrative. However, today, the Russian Orthodox Church’s support for the war in Ukraine showcases that religion can serve both as a tool for liberation and for perpetuating violence. In your opinion, despite these conflicting roles of religion, where do you believe humans will consistently find motivations to fight for their freedom?

While the Catholic church has not recently been perceived as a political force in the west, in Lithuania and Poland it was the sole source of organized resistance during the middle and late Soviet period. It was the vehicle of resistance. But we know religions have been used in various ways, including to support tyrannical regimes. In other words, religion in and of itself can be either a force for resistance or a collaborator in the apparatus of repression. Humans will fight for freedom as long as they can find the means to do it, but we know resistance can be crushed and ground down over time if the regime is brutal enough and willing to keep up the pressure. Resistance can also evolve. After the suppression of the Lithuanian partisans by the late fifties, Lithuanians practiced a form of resistance by acting deliberately through culture, in song and poetry, theatre and even academic pursuits, these in addition to acting through secret religious structures. The desire for freedom is very strong among those who are not willing to accept whatever a regime dictates to them, but the courage to fight is limited to a few, and the power to persist can sadly be ground down over time. Still, resistance can spring up again. Poland and Lithuania disappeared from the maps after their partitions among Prussia, Austria Hungary, and Russia in 1795. But rebellion rose up a generation later, in 1830, only to be crushed. Then it arose again in 1863, only to be crushed again. But both Poland and Lithuania reappeared on the maps after the first world war, over 120 years later. These actions give me hope for political resistance over longer periods of time, even after a situation looks doomed. I just hope that Ukraine will get the help it needs to assert its right to existence now, rather than later, that it will not fall under the current tyranny of Putin’s Russia.