With my novel, Underground, launched into the world, it is time to think of the next novel, which I have been hankering to get to.

There will still be a lot of talking about Underground and the partisan war because I have media appearances and festivals to attend in the fall, but just now I can get into the research on the new novel and expand the pages of the new book that I have already written.

The new novel’s working title is Fear no Fall – this is a thematic guideline for me, taken from John Bunyan, although I am not sure I will want to keep the title in the end (I lean toward Things Fall Apart as well, but it has been used so often).

| He that is down needs fear no fall, He that is low no pride… |

The novel will be set in in the murky world of espionage and counter-espionage among the Russians, Poles, Germans and Lithuanians from 1921 until 1923, when it still seemed like a determined man might seize a nation, or create an empire. After all, D’Annunzio was the poet who seized Trieste, Pilsudski the socialist bandit who became the father of Poland, and Lenin the failed seminarian (released from a German jail) who created the Soviet Union (with a little help from his friends).

My main character might open by saying something like this:

I was a self-made man who was building a self-made world without any of the hypocrisies of the past. After the old world collapsed, all we needed to do was hammer out the rules for a new one and play by them, and we’d build a better future. If our enemies would let us. If they didn’t, we’d have to outsmart them.

While I have done a lot of research and I have the story roughed out in my mind, I continue to read background in Lithuanian and I stumbled across a remarkable memoir by a writer who is entirely unknown outside Lithuania, and probably barely known within it.

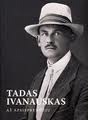

The book is called Aš Apsisprendžiu, written by the late Tadas Ivanauskas (1882 – 1970), who came from the baronial ruling class of of Lithuania in the czarist period and lived through dispossession in the Lithuanian independence period and then repression in the Communist era.

Through all this, he managed to be one of the men who created Kaunas university and was what can only be called an ecologist avant le mot, while at the same time a biologist, hunter, and prose stylist.

His ruling class was destroyed, so he is interesting as a representative of the Polish-Lithuanian rulers, (repressed under the czars) whose stories are not well known.

For example, in the period after the 1863 uprising, Catholics were forbidden to buy land. The regime hoped the Lithuanian/Polish ruling class would eventually have to sell to Russians (Orthodox Christians) and disappear. In Ivanasuksas’s family, the Lithuanian family manor lay near Lida, which was Polish between the wars and Belorussian after 1945. They dud not sell, but were driven by the reds during the revolution.

Ivanauskas describes his childhood in the manor with a richness of detail I have not read since Ceslaw Milosz’s Native Realm. With great charm, he describes the interior of the manor where they huddled around the ceramic stove while outside the birds could be seen pecking dried seeds from the pods of tall grasses sticking out of the snow. He describes characters such as “the smoker” who lived in the smokehouse while the meat was being prepared and smelled of smoke all day long. Young Tadas wandered out into the fields like some kind or Wordsworth, all clean and curious in nature. Outdoors-men of the time were hunters, and he became one too, in particular looking to find birds to shoot and mount for the manor room devoted to stuffed animals.

He did not do well in high school in Warsaw because he missed his home so much and detested the forced religiosity of the place, but he prevailed in St Petersburg where he studied science and eventually created a thriving business in providing universities and museums with skeletons and various other specimens required for the study of biology.

Why does he matter?

First, the gorgeous detail in the work is not to be missed. But beyond that, he represents what was swept away by the revolution.

Furthermore, he is interesting because he represents a place and time where language did not determine nationality. Most locals considered themselves Lithuanians, but the upper classes spoke Polish (and Russian with the government) and the lower classes spoke Belorussian. There were some Lithuanian speakers, but one had to travel some distance to find their villages.

But why does he matter to my novel? Because his is the world that existed before my spies try to make a new one. He is one of the ones who will lose (but arguably gain as well by adapting his skills to the new world.)

The prose is so good, that his story of the family boys travelling by cart with their uniformed driver and the dogs to a distant estate for a few days of hunting rivals the prose of Tolstoy’s hunt scene in War and Peace.

And yet the man was a biologist! So much talent to spare. So much beautiful writing hidden in the shadows. He’ll be a big help to me.

In the following weeks, I’ll talk about a few of the other books that I am using. The heart of the matter wil of course lie with Jonas Budrys, his espionage memoir called Lietuvos Kontrazvlagyba, but there are many other excellent sources.