Lithuanian partisans captured by the MGB in the postwar period were sometimes turned into provocateurs or double agents – few could resist the intimidation and torture used against them in interrogations. Some collaborators were more thorough and enthusiastic in their work than others. Among them were Juozas Deksnys, described in earlier posts, and Algimantas Zaskevicius (reported to have contributed to the capture of 300 partisans).

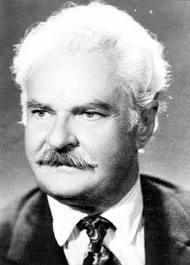

But the most famous of them all was Dr. Juozas Markulis, who taught medicine at the university of Vilnius.

Markulis was born in the USA but returned to Lithuania to complete studies for the priesthood. He never took religious orders. He was handsome and attractive to women, and he shifted instead to officer training in the military and finally into medicine in 1940. He joined the LLA, an underground Lithuanian resistance organization in 1941.

The organization was smashed by the Soviets at the end of 1944, and its archives fell into their hands. Markulis may have been identified at this time – he certainly was turned at this time.

The partisan underground lacked intellectuals – many of the fighters were the children of farmers, and Markulis insinuated himself into a local regional partisan unit where he was much beloved and looked upon as a father figure.

Markulis had two strategies – to unify the partisans in the country and to convince them to move toward passive resistance, tactics that were beginning to work. He was convincing to the partisans and impressive to his MGB superiors, writing long and detailed reports that showed he had an excellent memory for detail.

Working under intense pressure, Markulis could not avoid making mistakes, and one of them was permitting the MGB to arrest Jonas Deksnys, who had been instructed by his brother to maintain ties with no one but Markulis.

Thus it became clear that Markulis was a collaborator and spy and Juozas Luksa himself went to Vilnius in 1947 to execute him, but Markulis escaped.

He lived in Leningrad until 1953, when the partisan movement had been destroyed, and then returned to teach at the University of Vilnius.

His motivations remain opaque. He died in 1988, just before Lithuania regained its independence. His legacy is a name synonymous with treachery – he is the Benedict Arnold of Lithuanian to those who know the story of the resistance to the Soviets.