REVIEWS

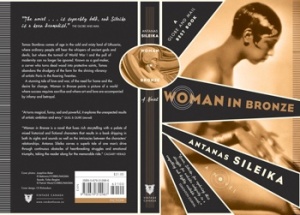

Antanas Sileika; $34.95 cloth 1-55022-620-7, 400 pp., 6 x 9 , Random House Canada, Aug. 2004

According to the locals, the town of Merdine is the safest place on Earth to practice adultery. After committing their sin in the ruins of a castle at the top of a hill, a couple can simply roll to the bottom and confess in the church below. Such is the last vestige of glory associated with this rainy Lithuanian Macondo imagined by Antanas Sileika in his new novel, Woman in Bronze.

Sileika, the artistic director of the Humber School for Writers, is a craftsman of great heart and integrity. This is a novel of ideas that never loses touch with the basic humanity at its core. At turns magical, funny, sad, and powerful, it explores the unexpected results of artistic ambition and envy.

Set in the 1920s, Woman in Bronze follows Tomas Stumbras, a young and ambitious sculptor, as he is chased out of Merdine after a disastrous affair with a servant girl. Happy to be out of the largely artless town, he slowly makes his way to the artists’ communities of Paris. These two places and their inhabitants could not be more different, but Sileika finds the common ground, with each place echoing the other. Lithuania, with its constantly shifting borders, is being pulled apart by the great nations of Russia and Germany, while Paris is in an artistic upheaval. There the great forces are the famous artists, gallery owners, and collectors who have the power to change lives, sometimes with a single word.

Tomas and his two roommates, fellow expat art students, manage to scrape together a living while competing to see who can sell one of their pieces first. And, since this is Paris, their art must also compete with their love lives. The results are surprising, tragic, and sometimes beautiful. It has been seven years since Sileika’s last book, a collection of linked stories entitled Buying on Time. The novel turns out to have been worth the wait

– Ken Hunt

Globe and Mail

Not so long ago, a friend of mine published a novel set, in part, in Ireland, and he remarked to me that of all the questions he got about the book, the most common was, “You’re not Irish ….. why did you set your novel in Ireland?” This was a pointedly Canadian query, one that expressed anxiety that it was impolite to write what you didn’t know. His answer — “because it fascinated me” — wasn’t particularly well-received.

Antanas Sileika’s new novel is set in a fictional Lithuanian town and in Paris, and despite his street-cred (he’s a Lithuanian-Canadian), he may find himself fielding the same kind of questions. Woman in Bronze not only dares to reimagine a heavily imagined place and time — Paris in the ’20s — but it has real-life characters cavorting with Sileika’s hero, a green sculptor fresh from rural Lithuania. When he abandons home, the young man not only has an encounter with the Polish war hero Josef Pilsudski, but once in Paris he meets Josephine Baker, Maurice Utrillo, Jacques Lipchitz and a host of other Jazz-Age notables.

The hero of Woman in Bronze, Tomas Stumbras, is a bad son. A crummy farmer, he’s got a yen for wood, which he has the talent to turn into miniature gods. But when his strange form of devotion fails to save his family’s farm, as well as the woman he loves, he quits home and goes to find his fortune, first in Poland, then in Paris.

In the City of Light, he becomes a carpenter for the Folies Bergère, where he meets Josephine Baker, and is ensconced in a world of struggling artists. He begins to feel at home for the first time, even though the hard times waiting for him and his friends could make a troubled existence on a farm look preferable.

Stumbras, who has already apprenticed in Warsaw, is looking to make the transition from craftsman to artist, and, with his two artist flat-mates, is waiting for fate to touch him on the shoulder. When he earns the commission to do a bronze of Josephine Baker, he thinks his way in the world is made, but a visit from a fellow old-country sculptor convinces him that his true voice is in a form that owes more to home than to the inspiration of Paris.

The novel, written in a deceptively easy prose, is superbly told, and Sileika is a keen dramatist. He also has a rather sly sense of humour, such as when the Stumbras family returns from church one Sunday morning to the rare and mouth-watering scent of roasting meat, only to find that Tomas’s grandmother has thrown herself into the huge bake oven in the middle of the house.

The scene is characteristic of the novel’s pairing of the sublime and the tragic; these tonal poles are its real subject, as the choice to spend your life making art inevitably sends the artist shuttling between them. The irony of young Stumbras’s choice to leave home is that he cannot leave his passion behind, and so drags his fate behind him. In Paris, he will lose another beloved (in a fashion significantly similar to the first) and his brothers-in-arms will suffer as greatly as the ones at home.

What is joyful about Stumbras’s quest is that he manages not to let go of his will to make something beautiful, and Sileika follows him through his apprenticeship to his maturation as an artist.

In making his first great work, Stumbras discovers the triumph of controlling one’s life and expression, and even when his achievement is ruined by outside machinations, he knows he has found his place on earth.

It’s a selfish quest, one that leaves a trail of betrayed and dead behind him, and the discomfiting choices in this novel are what makes it daring, not its setting or its cameos. Stumbras’s evolution parallels that of any culture, personal or national: Good sons and daughters turn away from their traditions, they let the old ways wither. And their guilt is never enough to trump their desire.

Perhaps it is this that makes some people nervous about our literature branching out well beyond home: It feels like a betrayal. Although we’re a country of readers famous for waking up one morning and realizing that even the Germans (well, especially the Germans) were reading us, our dirty secret is that we don’t actually know how to feel about it. Who are we, after all, to write internationalist books that even the Europeans like? It is a rite of passage to abandon home, and to act out of passion rather than duty. Woman in Bronze is a passionate book that does honour to all its homes.

– Michael Redhill

Other Comments About Woman in Bronze

Woman in Bronze, the third novel from Canadian Antanas Sileika, is a wonderfully engaging story of a young artist’s extraordinary journey from war-torn Europe to Bohemian Paris during the roaring ’20s.

– Calgary Herald

Bravo, Sileika, for capturing this struggle for artistic integrity in a compelling and highly readable novel.

– Edmonton Journal

The novel never loses an underlying intelligence that repays meditation on the part of the reader, a process aided by a prose that keeps itself in trim order

– Toronto Star

Sileika has proven himself to be an adroit storyteller

– Victoria Times Colonist

The successes of Woman in Bronze — its evocation of a bygone era, the story’s tragic sweep, and the kind of high romanticism that sees the hero turn away from his moment of triumph — have a grandiosity and pathos any verismo composer would love

– Vancouver Sun

Toronto novelist Antanas Sileika infuses everything he creates with an intelligent, human touch that makes his writing a pleasure to read.

– Books in Canada